Interdisciplinarity at M&B

Interdisciplinary dialogue allows to transcend the limits of one’s own discipline, to see the bigger picture by synthesizing different schools of thought, to jointly comprehend the complexity of man and nature. For some years now there has been a broad academic and education-policy consensus that interdisciplinary work is fundamentally well-advised and important. The brain and the human mind in particular call to be understood and decoded by the coordinated research efforts of scholars of the humanities and sciences. It is also clear that interdisciplinary thinking should be at the forefront of how we educate the upcoming generation of scientists. But interdisciplinarity is not a value in itself. And the concrete implementation of this aim, to conduct teaching and research in an interdisciplinary fashion, presents a whole series of challenges.

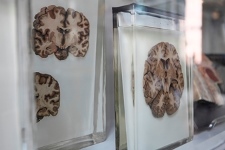

When in 2005/06 a group of scientists specializing in different subjects and originating from the Berlin metropolitan area (including researchers from Potsdam, Magdeburg and Leipzig) teamed up to write a proposal for the Berlin School of Mind and Brain within the framework of the Excellence Initiative, it came about as a response to a certain degree of pressure. Due to recent rapid technological developments in the study and representation of brain activity (e.g., positron emission tomography, functional magnetic resonance imaging) it had become clear that research which strives toward a comprehensive understanding of the brain and mind raises extremely complex questions which transcend disciplinary borders and cannot be satisfactorily answered by philosophy, neurobiology, psychology or linguistics alone.

Many of the proposal writers involved were part of a younger generation of researchers and at the time of writing the proposal were only in their thirties. But they, like the more senior proposal writers, had been compelled or forced to study two or even three disciplines in the course of their scientific careers, in order to be able to take a well-founded approach to the relationship between brain and mind: e.g., psychologists and medical clinicians would complete a course of study in philosophy, while linguists took degrees in psychology.

Consciousness, free will, perception or language – the proposal writers agreed that researching such complex topics would necessarily entail more than just a new kind of interdisciplinary cooperation in the future. Rather the next generation of researchers would have to have been previously trained in an interdisciplinary fashion. Five overarching topics were identified as research and training focal points for the graduate school: Perception, attention, consciousness (Topic 1), Decision-making (Topic 2), Language (Topic 3), Brain plasticity and development across the lifespan (Topic 4), Brain disorders and mental dysfunction (Topic 5). In 2012, Human sociality and the brain (Topic 6) was added.

The graduate school was therefore set up with the aim not only of continuing the education of talented young scientists with an educational background in philosophy, psychology, biology, linguistics, medicine or neuroscience in their own discipline, but also of educating them across the whole breadth of mind and brain research. Doctoral candidates should as a result be competent to carry out their own projects at the knowledge interface between the humanities, social and natural sciences.

At the very beginning of the Mind and Brain venture it was decided that students should apply exclusively with their own projects, which are to exhibit even at this early stage an interdisciplinary research approach. A particular challenge is posed by the “matching” of students and their future (at least two) supervisors. The latter, as a basic rule of the graduate school, always include a representative of the “Mind” side and a representative of the “Brain” side.

In a multi-stage selection process, during which representatives of all six topics and disciplines are involved in the form of the selection committee, around 25 candidates are selected to present their projects and come to interview. In this part of the selection process, there is often in-depth discussion between the committee members, since the notion of “interdisciplinarity” is ultimately under constant negotiation, even at this stage, i.e. what it means in relation to a specific project and how this can be implemented in the context of the given research topics and opportunities at the graduate school. At the end of the selection process the committee decides on the new doctoral candidates who are admitted to the graduate school each year and makes suggestions for supervision.

The elaborate admissions procedure is significant for the success of interdisciplinarity, highlighting as it does the indispensable willingness of doctoral candidates, supervisors and scientific management alike to deal with unusual structures and issues with a view to engaging in the unconventional work described above. Just as they are developed with a high degree of creativity and autonomy, the doctoral projects are supervised with an open mind and willingness to negotiate and they are welcomed in spite of the extra work and occasional problems that such a great diversity of topics and methods inevitably engenders.

However, we have also realized from the beginning that, our deep commitment to interdisciplinarity notwithstanding, it is essential to retain the core competencies. Scientific contact with the primary branch of study should of course not come to a stop. Therefore, our graduate school also offers support when it comes to visiting disciplinary national as well as international symposia, summer schools and special courses. We encourage doctoral candidates to attend specialized academic conferences in order that they may have the opportunity to prove themselves in front of a trained expert audience and keep testing their ability to engage in disciplinary academic discourse.

To sum up: What exactly “interdisciplinarity” means for our graduate school cannot be answered authoritatively, but rather has to be negotiated continually. Accordingly, discussions on the subject are intensive and continuous among teaching staff, supervisors, and management as well as doctoral candidates.